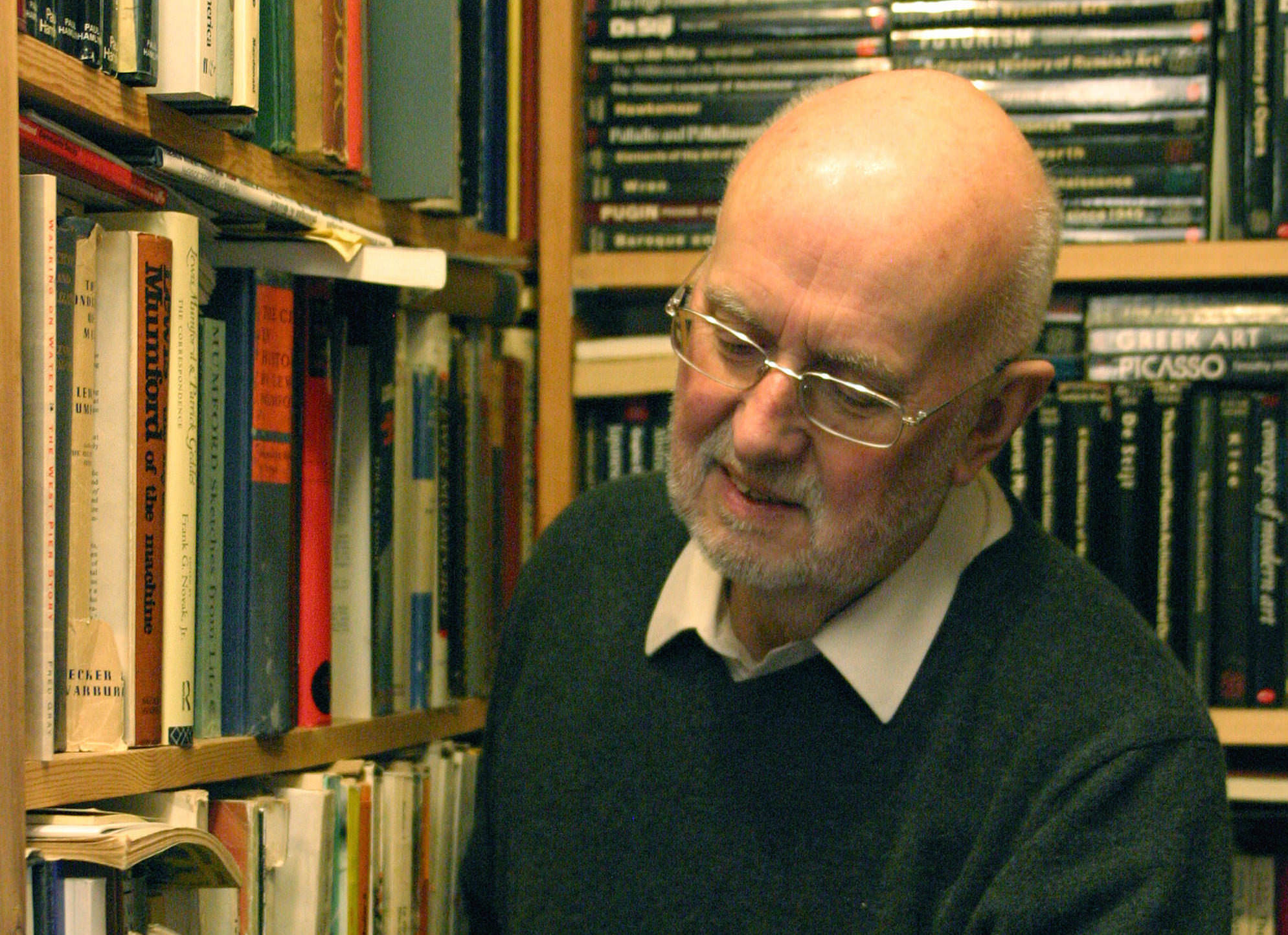

By Dennis Sharp. Photo: Alberto Sartoris, La matière et le dessin.

Recently searching through an architect’s library I came across Alberto Sartoris’ famous encyclopaedia Gli elemente. . . which I hadn’t looked at for years. It was partly incorporated into Architecture in the 20th Century by Taschen in the late ‘90s but it doesn’t seem to have ever been published fully in English. Dennis Sharp had the good fortune to interview Sartoris about his book and some of this interview was published in Building magazine (1983). The following article is a new version submitted recently for publication in The Architect, the official journal Kamra tal-Periti, Malta.

It would be impertinent perhaps to suggest that Alberto Sartoris has been overlooked in Britain. Certainly it appears that he has been largely forgotten. Although a lifelong corresponding member of the RIBA, his books have never been translated into English. However, any architect worth his salt will know his clear drawing style and any serious student of modern architecture will know his classic books on Functionalism.

Born in Turin, Sartoris trained as an architect in Switzerland and became one of the leading theorists and writers of the Modern Movement. Sartoris was the man who put the word “functionalist” into the architectural vocabulary. For him it meant something specific: “The term functional”, Sartoris said, “is an approximate term that justifies our movement . . . it is a term that suits all styles but the way I used it, you see, it meant this particular movement, of pure art. It had nothing to do with lyrical rationalism, geometric and linear – the kind that people most objected to at the time…”

«Our” movement in this context means the modern tendency started by the group of architects under Le Corbusier. The Functionalist Group was officially founded at La Sarraz in 1928 and called CIAM (Congrés Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne). CIAM, Sartoris stressed, operated at “an international level” and today it is still “being carried on by the young architects from Ticino, like Mario Botta”.

Alberto Sartoris was Le Corbusier’s choice as the Italian representative to CIAM. He was not popular with his own countrymen who placed less faith in Italian support for modern architecture than Corbusier or Karl Moser. Sartoris recalled that they “looked for government support. The congrès was set up because Le Corbusier and the major architects of the time thought that governments’ support would be decisive in the development of the new architecture”.

Sartoris revealed that Karl Moser “also thought that one day Mussolini would ask Le Corbusier to build a new town” in Italy. In fact, he did not.

Moser’s position in the early years of CIAM was critical and it was to him that the Italian architects wrote to protest about Sartoris’s membership of the congrès. “Sartoris cannot represent us because he does not belong to the architects union or to the Order of Fascist Architects; we do not want him as our representative”, wrote Piero Bottoni, a Communist.

Throughout all this Sartoris himself remained a firmly convinced Modernist and grew in stature within CIAM through his numerous writings and his innumerable projects. He traveled widely too at the turn of the 1930s and was constantly broke, although he was always considered wealthy because of his sartorial elegance and self-confident gestures.

Now over 80, he does not seem to have lost any of that sophistication. He remembers those days with good grace: “I could not have afforded a secretary . . . nor draughtsmen. In fact, later when I began getting more commissions I never employed draughtsmen, only students worked for me! And all the drawings were done by my own hand.” He has produced 700 or so major schemes of which only about 50 have been built.

He began practicing in the mid-1920s and soon after designed what he now calls “the first Italian modern building” in 1927 – the Artisans Pavilion in Turin (since destroyed). But his first major building project, for the Turinese silk magnate Gualino, was a splendid theatre (often dismissed by critics as neo-Classical) which according to Sartoris “was in fact . . . really mysterious and metaphysical – it was red, grey and black.”

The early work for Gualino will form the subject matter of a major exhibition on Sartoris’s metaphysical and coloured architecture in Turin later this year.

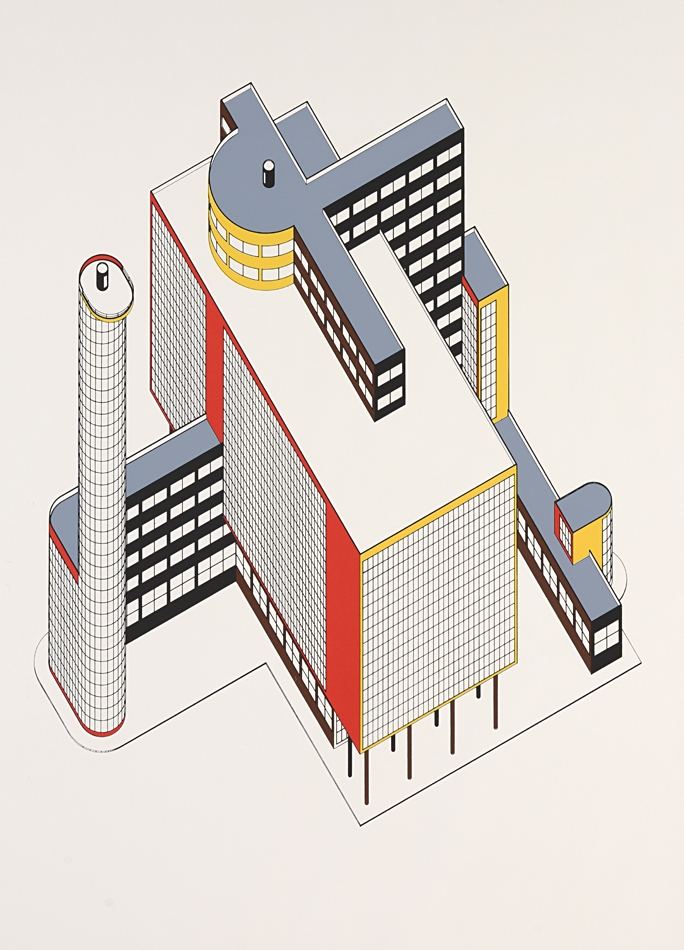

Besides his distinctive “axonometric” drawing style – reproduced for posterity in his numerous publications – it is probably his use of colour that makes his work so memorable and important.

He recalls that he “used colour when it was difficult to produce it” and he confesses that his interest in it derives as much from his work as an art critic as from his interest in the architecture of the Dutch De Stijl group. “For me colour represents the fourth dimension of architecture, it provides its dynamic quality and aesthetic character. Black gives depth, yellow gives sunshine all the year.”

Sartoris wrote, in a small publication on the Italian visionary Sant ‘Elia, that “architecture had been invented by painters, not by architects”.

How does he view his lifetime as a chief propagandist of Functional architecture and his own postliminy? He replies with characteristic, and indeed justifiable, confidence: “I have not actually built many of my projects – but all my ideas, all my axonometrics, all my principles can be seen realised in other architectures not built by me. I am happy about this.”

0 comments on “Sharp Cuts -Some Thoughts on Alberto Sartoris”