By Jean-Louis Cohen

Log 6, Summer 2005

Photo: Shayne House / Unsplash

Three different Berlins live within me. Several literary tropes could be used to recount the relationship I have entertained with these adjacent or successive cities for nearly 45 years, nurtured by a variety of experiences that seem to measure time past, from childhood to mature age.

I could indulge in a monologue à la George Pérec, enumerating a litany of «I remember» phrases as he did in his 1978 booklet Je me souviens. It could become something like:

-I remember the piles of rubble and the streetcars zigzagging between them on Alexanderplatz.

-I remember the pink and yellow packages of biscuits on the shelves of the HO (Handels-Organisation) supermarkets.

-I remember the beard of Walter Ulbrich on the posters, the medals, and the buildings.

-I remember, decades later, the fresh rubble of the just-fallen wall and the gray landscape suddenly emerging . . .

I could reminisce à la Proust and evoke, like in À la recherche du temps perdu, simple sensual memories, from the smell of coffee made with cereals sipped in the East in the 1960s and the chemical taste of “democratic” candy to the first swallow of Berliner Weiße mit Schuß on a cruise-boat of the Weiße Flotte sailing on the Müggelsee. I could reconstruct memories of human relationships between politicians, planners, and artists that shaped the various milieus in which I evolved during all these years. I could even risk reenacting, à la Walter Benjamin, a piecemeal but deeply moving Berliner Kindheit um Neunzehnhundert, returning mentally to streets I had taken in the East and in the West, and along which fragments of past and present societies were to be perceived.

Remaining on a firmer ground, I might simply stick to the socially constructed role of the “architectural historian”, that is, an historian who is himself shaped by architecture, and comment upon the remarkable urban landscapes whose intricacy has made Berlin in the past three centuries. In retrospect, what I perceive in my memories of the city is the slow revelation of the path leading from childhood to adulthood. In a way, the shaping of my own split identity of architect and intellectual can be measured by my changing relationship to the Berlins I have met. So these lines are not so much about the making of history than about the making of the historian writing them.

French novelist and publicist François Mauriac, fresh from his Resistance experiences, affirmed in a celebrated statement that he so enjoyed Germany that he was delighted at the idea that there were two of them . . . Building upon this assumption, I could say that my love for Berlin was so intense that I was thoroughly thrilled by the side-by-side existence of two of them. Mediated now by readings and sometimes by research, my perception of Berlin remains permeated by this dual fascination, which the reunification of the city has not erased.

Grasping Berlin as an entity has always been difficult, not least to observers coming from Paris. Writing in 1882, Symbolist poet Jules Laforgue insisted on the monotony of its streets, Unter den Linden included, and viewed them as “a double hedge of monuments, painted in grey, naked, cold as a group of barracks.” The exoticism of Berlin did not reside in its Germanness, but rather in the Americanism of this “Chicago by the Spree.” The sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who had spent one year in Berlin before 1914, would write retrospectively in 1934 that “to everyone who had never visited the United States, Berlin could give a good idea of what were American large cities, which had grown in several decades following an unprecedented tempo.”

Berlin 1: Eastern exoticism

The first Berlin I met was limited to the Eastern sector and the earliest encounter took place in July 1961. To a certain extent, the exoticism was an exact mirror image to the one spotted by Halbwachs. The signs that most struck me then were not signs of an America I both hated and was fascinated by as they were related to the Soviet occupation of the city in its many manifestations, from the denominations of streets to the presence of actual Russian military hardware and cars throughout the city. I belonged to a group of Parisian teenagers who had been invited to stay in the Pionerpark Ernst Thälmann, a sort of small children’s republic located near Köpenick, in the southeast of East Berlin. One month before the erection of the wall, we were taken to the Brandenburg Gate and to the Russian Memorial in Treptow, and subjected to an intense political bombardment insisting on the perverse attempts of the West to colonize the “people’s democracies.” Coming from a leftist background, and perceiving the Red Army as the great force that had freed Europe, I subscribed without pain to this diatribe.

Some strong architectural memories remain from that summer: the ruined cathedral on the Lustgarten and the poignant twin churches on the Gendarmenmarkt; the powerful cliffs of the Stalinallee, which had just been renamed Karl-Marx Allee, and the construction of its western, functionalist extension leading to the Alexanderplatz. Looking at the blurred photographs I made with an obsolete folding large-format camera, I also realize that, attempting to shoot Bertolt Brechts’ Berliner Ensemble on the Fränkelufer, I unwittingly included in the frame Hans Poelzig’s Grosses Schauspielhaus… It would be several years before I entered the world of architecture and understood the meaning of this big drab-looking box. Even less did I know that the headquarters of the German Democratic Television, where I was enrolled in a children’s program entitled, if I remember correctly “Aktuelle Kurbelwelle”, (literally translated, “Current Crankshaft”) were installed in Adlershof, near the former Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt, a stronghold of Nazi modernist design. I can now further identify this building from 1950 as Wolfgang Wunsch’s unique combination of Modernist and Heimatstil.

I returned to Berlin in 1962 and 1963. In those years, the group was staying in Prenden, not far from Bernau, and in all architectural innocence, I was taken to visit the trade union’s school in that city, completely unaware that the ADGB school was the most refined statement of Hannes Meyer’s functionalism. I was much more interested in spotting the MiG-21 and the Il-28 airplanes that were flying over the camp and the town, or by the poignant visit to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In 1967, preparing a shift from the study of mathematics and physics to architecture, I had a sharper view of buildings. Stationed that summer in Werder, in the vicinity of Potsdam, I discovered Sanssouci and the ruined buildings in the park. The political highlight was a visit to Cäcilienhof, the English-looking mansion where the Allied conference had taken place in 1945 after the collapse of the Reich. How could I have known then that the house had been designed in 1912 by Paul Schultze-Naumburg, the figurehead of German traditionalism? Another day, following a trip to the DEFA (and former UFA) movie studios in Babelsberg, a party was organized by film students – most of them Latin American – in their dormitory. The combination of beer and some unspecified liquor caused my first full alcoholic intoxication, but the little house with a large roof perched over the river struck my imagination. It would take me many years to realize, when I returned to that spot in 1992, that this was none other than the Aloïs Riehl house, the first building of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe . . .

After all these unconscious encounters with architecture, the subsequent years would lead to more explicit episodes. Inserted as “the student” in a group of Paris professionals visiting East Berlin in 1972, I was able to look in detail at buildings I had by then identified – Poelzig’s Schauspielhaus, for one – and also to convince our hosts/guides to let us go to Dessau to look at the Bauhaus buildings. Complete wrecks: the workshop wing of the school could hardly be recognized, as the glass surface had been completely walled in, and the Meisterhäuser were off-limits, as they were being used by Soviet officers. On the way out of Berlin, we had managed to have a peek at Erich Mendelsohn’s Luckenwalde factory.

The following year, I acted as the designer for the French “club” at the World Youth Festival taking place in East Berlin, and this time I was directly confronted with the architecture of Peter Behrens, as the building I had to decorate was his Elektra rowing club, built for AEG in 1912, whose cable factories in the East had since been rechristened KWO (Kabelwerk Oberspree) and the Elektra club was then known as BSG (Le Corbusier drafted the plans for this building while working for Behrens, during his stay in Berlin, in 1910.) On the day before the opening, I fell down from a ladder trying to explain how to attach a curtain, and broke an arm. Lacking in any confidence in respect to “socialist” surgery, I asked to be flown back to Paris. The security people led me through a very special way out. I entered the Friedrichstraße checkpoint, only to be brought through labyrinthine corridors and stairs to a narrow door. Once opened, I found myself on the platform of the West Berlin U-Bahn and went on to Tegel airport. It would still take some time before I firmly set foot in the West.

Berlin 2: Western creativity

My second Berlin was centered on the Western side of the city, which I discovered at ground level some 15 years after my first visit to its Eastern counterpart, around 1976. I had seen its expanses since the earliest eastbound trips from the S-Bahn tracks without ever leaving the train. This time, politics was no longer the initial excuse, and part of the exoticism was gone. I was by then a young designer and scholar, so architecture and history were the issue from the outset. Captivated by various aspects of German modernism, I started looking at the neighborhoods of the “neues Bauen.” The then rather derelict Siedlungen of Bruno Taut in Britz, Onkel-Toms-Hütte, or Freie Scholle, the Siemenstadt residential scheme, and the scattered modernist houses became focuses of photographic excursions, extended sometimes to Schinkel’s buildings in Charlottenburg and in the Pfaueninsel. More inclined to admire Behrens and Mies van der Rohe, whose work I tracked in all the western districts, to the far end of Dahlem and Zehlendorf, I nonetheless conscientiously visited all the Scharoun structures, shunning the late Gropius edifices.

The experience of Berlin in the last decades of the Cold War was sometimes an amazing one. I recall having taken the French military night train, arriving every morning from Strasburg, that crossed the Iron Curtain sealed and unhampered by controls. It was a sort of umbilical cord connecting the French sector of West Berlin with its West German mainland. But at the same time, the Technische Universität and the Hochschule der Künste were thriving with innovative historical research and design, and exhibitions such as the 1977 Tendenzen der Zwanziger Jahre or its alternative companion Wem gehört die Welt? were promoting new views of Weimar Germany’s culture in sharp contrast to the clichés still accepted outside of Germany.

Also, new ideas in opposition to mainstream city planning and urban renewal were challenging the idea of the tabula rasa and also the practice of expensive, antisocial restoration. This led to the project of the Internationale Bauausstellung, scheduled for 1984 (and held eventually in 1987), which moved beyond simply establishing new standards for city expansion and tried to define concepts for the reconstruction of urbanity in areas left vacant by the bombs or in blighted, impoverished neighborhoods. Together with Bruno Fortier, we introduced the new Berlin programs to the main planners in Paris and organized debates that led to a reappraisal of the French approach to slum clearance and urban design.

During those years, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, I frequently returned to “my” first Berlin, on the other side of the wall. I was now ready to take time to look at the main structures of Schinkel in Mitte that were finally being restored (the excuse being the bicentennial of his birth), and also to discuss with Hermann Henselmann the details of his early-1950s designs for the Stalinallee in the slightly more relaxed atmosphere of the late-Honecker GDR. The desperate attempts of some East German architects to introduce some flexibility into the rigid, heavy prefab system used ad nauseam – in building the new district of Marzahn, for instance – were leading to almost grotesque uses of the pre-cast concrete “Platte” – heavy panel – for urban infill or imitation Gründerzeit apartment houses in Mitte. A sort of “Ost-Modern” language was appearing.

Berlin 3: rejoined and reflexive

The third Berlin I have encountered between 1989 and the present day is, of course, not the mere sum of the two previous ones. It was to some extent born out of a merciless selection of existing features when the wall was torn down. The most amazing phenomenon that appeared then was a sort of time-space collage: the separation between areas of Berlin lying on opposite sides of the same stretch of the wall could not be measured in meters or in feet, but in decades. Two cities a half-century apart had been suddenly joined together. Buildings from 1939, together with their closed stores, their half-vanished advertisements and streets with their cobblestones and lampposts from the same vintage were facing brand new offices or residences well inscribed in the 1980s…

I must admit the trouble I still have – and that Berliners have had – reconciling these two halves of the city. A television program I wrote in the fall of 2004 for France 5 forced me to focus my thoughts on the relationship between the city we see now and the former cities it very often masks. The constraint of time in a 26-minute program had the effect of producing a sequential narrative of short monologues shot in situ in front of major buildings or scenes. In these extremely condensed addresses, the lecturing historian was inevitably hiding the more intimate memorialist I had wanted to be. But the time spent with the crew helped me to reshape my memory and focus some thoughts on contemporary Berlin.

For instance, one still has trouble today imagining that trips that were impossible or very complex before 1989 are now easy and natural. Areas that were off-limits have become accessible: in an extraordinary reversal of urban fortune, territories that were peripheral both to the East and the West have become central to the recollaged city. Berlin has developed since its very foundation in the 13th century not as the sedimentation of urban composition, but through juxtaposition, and the acceptance of the division in the 20th century was to some extent eased by this aspect of the city’s history. Yet, the reunification of the triangular Friedrichstadt, from the Rondell-Platz (now Franz-Mehring Platz) to Unter den Linden, was essential in reviving the memory of Berlin’s urban structure.

The rearticulation of connections broken at all scales, from the narrow street to the railway or the freeway, has led to a new cohesion of the metropolis. But in terms of building distribution, the city has maintained its archipelago character: the cohesive force can bring about small islands, but cannot stitch together the whole. Since the 17th century, each addition of “Städte” and «Vorstädte» has shaped a city made of discrete parts, each with its own morphology, a city much closer to London, Los Angeles, or Tokyo than to Paris or Rome. This logic of the fragment has been interiorized, despite the accent put by the Senate administration on cohesiveness and urbanity.

One such island, the political center represented by the Reichstag, the new Chancellery and the collection of housing and offices built in the Spreebogen, achieves the austere, severe presence characteristic of democratic institutions. As if it were in continuity with axial plans made for Berlin ever since the 18thcentury, the east-west political composition is intersected by the commercial axis of the new Friedrichstraße, a collection of big, boring boxes that fail to generate any palpable urban life, as if the “double hedge” perceived by Laforgue had been reproduced. Similar remarks could be made looking at the recreated Pariser Platz, at the western end of Unter den Linden. The boxiness of the Adlon Hotel is inescapable, and strengthened by Günter Behnisch and Werner Durth’s new Akademie der Künste. Both Christian de Portzamparc’s French Embassy and Frank Gehry’s DG Bank allow for a certain guesswork, letting the spectator imagine, thanks to several indices, that their stern fronts are hiding interior surprises.

Contradictory perceptions of memory can be met on the square, from the literal reconstruction of previous buildings to the contemporary interpretation of destroyed institutions like the academy or the embassy, to completely new programs. Other objects are also dealing explicitly with the issue of memory, and incite me to consider, in conclusion, the present city in light of its memorialization efforts. Three buildings condense the problem of literal memory. The rather frightening Palast der Republik, stripped of its asbestos, has no other message to convey than to represent the best remembrances the East Germans –Ossies– have of the GDR’s cultural life. Consider the plan to reconstruct the Stadtschloss, a building of a less dubious architectural quality than the Palast, albeit one that would undoubtedly be difficult to rebuild with archeological correctness. Were the government to make good on the Bundestag’s promise to rebuild the seat of the rulers of Berlin, the resulting building would point to a series of meanings, from Prussia’s engagement in the Enlightenment to Hohenzollern policies of hegemony. I am not inclined to support the reconstruction of this formidable structure, and would compare its blasting by the East Germans after 1945 to the demolition of the Tuileries Palace in Paris after the 1871 Commune and the return to the Republic, a similar case of political iconoclasm. I believe, however, that Schinkel’s Bauakademie, which stood on the other side of the canal until the GDR destroyed it in the 1960s in order to build a mediocre slab for its Ministry of Foreign Affairs – now gone – has a clear significance in cultural and architectural history and therefore a more legitimate claim to recreation.

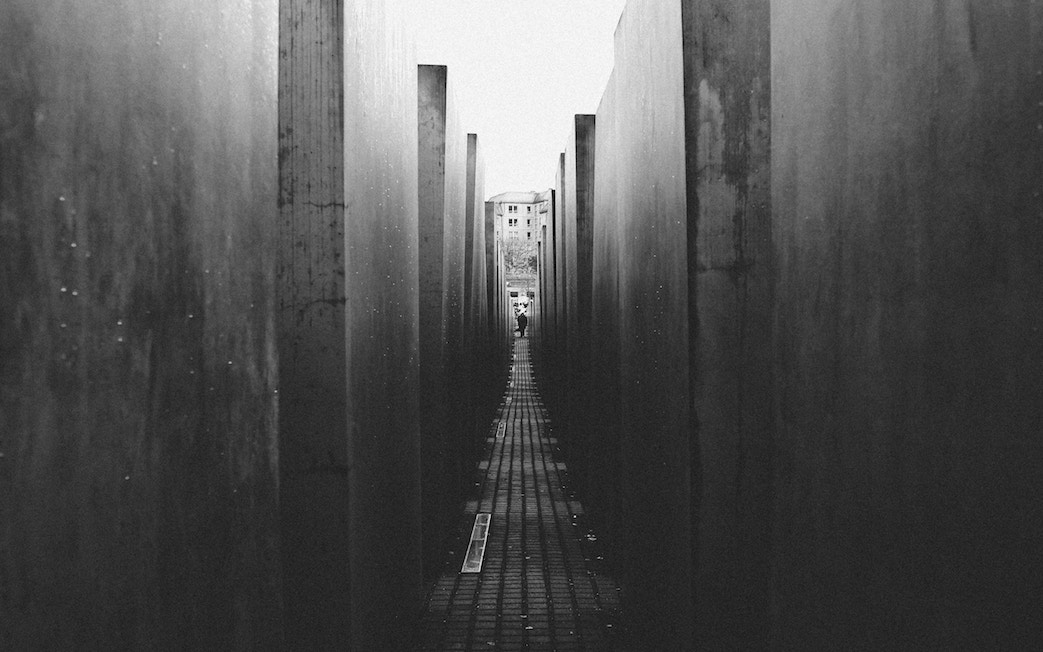

Remembrance is also at work in Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, whose plan belongs to the genre of «architecture parlante”, in this case, an architecture that talks only to airplane pilots flying over it. The metallic mass of the museum, as inserted in the south Friedrichstadt, is a happy reminder that the Jewish presence in Berlin was a fundamental factor of the city’s modernization. Though Berlin is a city still rich in built vestiges of Nazi-era architecture – some examples of which remain breathtaking, such as Tempelhof Airport – no single structure could be transformed into a Holocaust memorial, as the Russians had been careful to raze after 1945 the most emblematic palaces of the Third Reich. The meaning Peter Eisenman’s memorial takes in this context is a most compelling one, if one relates its field of stelae to Jewish cemeteries across Central and Eastern Europe. But I would also propose to read its tombscape as a scale reduction of all Berlin. The dialogue between the stelae and the alleys echoes the repetitive pattern of many districts of the reborn capital. For if something unifies the Berlins I know, it is perhaps this extreme variation of the “hedges” observed by Laforgue: Late-19th-century Mietskasernen, bars in the Siedlungen of Weimar, or the postwar functionalist ones and even the Stalinallee all belong to a genre astonishingly interpreted as abstract form, as if the city itself had been an actor in a tragedy. Strolling through the alleys of the memorial, I can project on the stone screens my own memories of three cities.

0 comments on ““Ich bin ein (dreifacher) Berliner””